Part 1

Introduction

1 The Government’s security and preparedness policy

Norway is a long country, but we are bound by strong ties. We live across the length and breadth of the country and we have a fundamental trust in each other and in the authorities. This community of trust and good, safe and vibrant local communities throughout the country are the most important building blocks of Norwegian civil preparedness. Different parts of the country and different groups in society may have different challenges with respect to preparedness. No matter where you live in Norway or who you are, society should be there for you in times of need. With this white paper, the Government is setting out a completely new direction in the development of total preparedness throughout Norway to strengthen the resilience of the entire population.

1.1 The need for a new security and preparedness policy

Norway finds itself in a more dangerous and unpredictable world.

Our situation is defined by the serious security situation in Europe as a result of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the war in the Middle East, and intensified global competition and rivalry between superpowers such as the US and China for military, political, economic and technological power.

Technological developments are challenging security and preparedness in ways we cannot fully comprehend. The digitalisation of society, use of social media and development of new technology such as artificial intelligence all contribute to this. Climate change increases the risk of natural hazards at home and can intensify migration and conflicts globally.

To address this development, Norway must strengthen its overall defence capability. The Government’s long-term plan for the defence sector heralds a significant boost to our military capability. The Government is now presenting a historic white paper on Norway’s total preparedness. In the white paper, the Government sets the direction for reforming for the civil part of Norway’s total preparedness and for civil resilience. We will ensure that civil society is prepared for crisis and war, and develop a society that supports military efforts and resists hybrid threats. This involves planning our response to acts of war on Norwegian territory as well as on allied territory.

Russia’s willingness to use military force to achieve political goals makes it likely that Norway will have to deal with an unpredictable and risk-taking neighbour for a long time to come. China’s closer strategic partnership with Russia and its support for the war in Ukraine are disquieting, while we depend on cooperation with China in certain areas to solve the greatest challenges of our time.

The use of hybrid activities makes the distinction between peace and crisis less clear, and challenges the conventional distinction between national security and public security. Disinformation, influence operations, covert investments in strategic businesses, supply chain disruptions, insider risk in private or public undertakings, as well as more frequent cyberattacks, have become commonplace in the threat landscape.

Hybrid activities are often employed over a long period of time and include both legal and illegal measures. Such activity is often carried out covertly through the use of intermediaries, and state actors increasingly use profit-motivated criminals to carry out operations. It can be challenging to understand, recognise, handle and counter such activity, and it affects us all. See further discussion in Chapter 7.

The public’s ability to distinguish between the truth and falsehoods is challenged. Hybrid threats may aim to create divisions between groups and destabilise society.

The business sector, which owns much of society’s critical infrastructure and plays a key role in important value chains, is exposed to cyberattacks, insider risk and foreign intelligence. Foreign actors may seek to disrupt basic services to the population and thereby weaken society’s resilience.

Municipalities are responsible for safeguarding the security of their local communities and are an important part of Norway’s basic preparedness. Crisis and war could challenge municipalities’ ability to maintain basic services for their citizens.

These developments and the complexity of the threat landscape require a more vigilant and resilient civil society. The general public, voluntary organisations, the private sector and local, regional and national authorities must increasingly recognise that security and preparedness are a joint responsibility to which we must all contribute.

The Government will ensure that society’s overall resources are better utilised both in the prevention and management of crises, and ensure close involvement of the private and voluntary sectors. During any incident at the high end of the crisis spectrum, society must have a preparedness culture and what it needs to handle various incidents and crises.

Greater demands will be made of citizens’ self-preparedness. The increasingly close link between the economy and security means that businesses must, to a greater extent, integrate national security considerations into their decisions. Municipalities must systematically plan for major incidents where society will depend on resources pulling together. Businesses, municipalities and county authorities must be able to make good evaluations to safeguard national security.

Strengthening society’s resilience to these developments requires a wide range of measures: regulation, financing, guidance, cooperation and self-preparedness. The sum of measures at different levels will contribute to awareness, knowledge and a shared understanding of the situation, and make us better prepared as a society.

At the same time, we cannot fully protect society against all threats. Incidents will happen. The measures we need to implement must be based on an assessment of risk, and the level of risk we have to accept and live with. We need to know which interests and assets we need to protect.

A long-term approach is important to addressing preparedness. The Government therefore appointed a Total Preparedness Commission in January 2022. The Commission has assessed the strengths and weaknesses of Norway’s current preparedness systems and proposed how society’s collective resources can and should be organised to further develop resilience and ensure the best possible overall utilisation of preparedness resources. The recommendations made by the Total Preparedness Commission in Norwegian Official Report (NOU) 2023: 17 Nå er det alvor – rustet for en usikker fremtid (The time is now – prepared for an uncertain future – in Norwegian only) are followed up through, among other things, this white paper on Norway’s total preparedness.

1.2 Basis for a new security and preparedness policy

The preparedness policy must be based on our strategic interests and utilise our advantages. At the same time, the measures must be based on an understanding of the vulnerabilities we face.

Norway is rich in resources, has knowledgeable citizens and a society where people trust each other and the authorities. The business sector, social partners and public authorities are used to working together. We must develop and protect a society where people and resources throughout the country pull together to prevent and handle crises.

Economic resilience is a mainstay of Norwegian society. A well-functioning business sector, trade and financial stability are prerequisites for maintaining the fundamental functionality of society. Norway is an open economy that trades extensively with the rest of the world. This makes cooperation and interaction with other countries important. Norway is a significant export nation, and we also have significant imports. During the pandemic, we learned the importance of international cooperation for gaining access to vaccines. At the same time, the threats we face today mean we must strengthen national control over critical infrastructure, natural resources, property and strategically important undertakings and value chains.

The High North is our most important strategic region and of major significance in the current security situation. Our freedom of action in the area is being challenged by Russia, while China is also showing increasing interest in the region.

Norway is a major energy nation. Following the war in Ukraine, Norwegian energy supplies to Europe have become even more important in the context of security policy. This makes us vulnerable to pressure and sabotage throughout the value chain.

With one of the world’s longest coastlines, we are particularly vulnerable to maritime covert intelligence activity. This challenges, among other things, our maritime industry and critical infrastructure.

Norway is a highly digitalised society. This is important for our competitiveness and innovative strength, but also creates vulnerabilities with great potential for harming society.

Norway is firmly rooted in a Western and European community of values and interests. NATO is the cornerstone of Norwegian security policy and crucial to our defence capability. Finnish and Swedish NATO membership opens up new opportunities for closer Nordic cooperation on security and preparedness. Norway’s most important trading partners are in Europe, and several important partnerships have been established in the field of civil preparedness. This international community is crucial to Norway’s security, but is increasingly being challenged by actors who seek to create division and weaken unity among Western countries.

1.3 The Government’s goals and priorities

The backdrop for this white paper is the most serious security situation in Europe since the Second World War. Through the long-term plan for the defence sector, the Government and the Storting (the Norwegian Parliament) have jointly adopted a historic strengthening of Norway’s defence. The challenges we face as a society also make it necessary to strengthen civil preparedness.

Since the Second World War, Norway’s defence has been based on the concept of total defence. The concept recognises that support and cooperation between civilian and military resources help Norway to counter and handle threats to society and the state. For civil society, this primarily concerns making better use of society’s collective resources. Central government and local authorities, and the business and voluntary sectors must collaborate more closely to ensure that resources pull together more quickly when a crisis strikes. The plans made by civil society must harmonise with military planning, and prioritise resources where they are most needed. Civil authorities, the Norwegian Armed Forces, private organisations and the voluntary sector must have a common understanding of the situation and conduct more training exercises together.

In light of the current security situation, this white paper emphasises work on total defence and the resilience of civil society in situations where the worst-case scenario occurs and Norway again experiences armed conflict or war. At the same time, the Norwegian preparedness model is based on total defence resources also being employed in ordinary preparedness for natural disasters, major accidents and other serious incidents. Strengthening preparedness for incidents at the high end of the crisis spectrum (see Box 2.9) will also help to strengthen society’s capability to prevent and handle other incidents.

A resilient, steadfast civil society is key to Norway withstanding a more acute and complex threat scenario. The Government’s work on strengthening civil society’s resilience is based on three primary objectives:

-

Norwegian civil society is equipped to deal with a crisis or war

-

Norwegian civil society is able to withstand hybrid threats

-

Norwegian civil society is able to support military efforts

In this white paper, the Government presents a number of measures to strengthen the resilience of civil society and help to achieve the Government’s primary objectives. These measures are based on seven strategic directions for the Government’s work, see Box 1.1.

Textbox 1.1 Seven strategic priorities for the Government’s work on security and preparedness

The Government will:

-

ensure settlement, good basic preparedness and vibrant local communities throughout Norway.

-

make better use of society’s collective resources in prevention and crisis management, including involving the business and voluntary sectors in preparedness work at the local, regional and national levels.

-

strengthen cyber resilience and national control over critical infrastructure and strategically important undertakings, natural resources, property and assets.

-

strengthen the population’s resilience and maintain a high level of trust in society.

-

strengthen security of supply, including food security.

-

ensure closer cooperation between the civilian sectors and the defence sector.

-

strengthen civilian capability to support allied military efforts within the framework of NATO and through enhanced Nordic and European preparedness cooperation.

Ensure settlement and activity in local communities throughout Norway

Settlement, activity and vibrant local communities throughout the country are vital for Norway. The Government will therefore pursue a comprehensive policy that ensures settlement throughout the country, enabling us to maintain a vibrant and sustainable society. The Government will ensure strong, local communities and good basic preparedness at the local level.

Ensure good basic preparedness in local communities

Prevention and good basic preparedness enable crises to be handled as quickly as possible at the local level. Municipalities play a crucial role in preventive work and managing incidents. The Government’s proposal that all municipalities should have or be affiliated with a municipal preparedness council will help to strengthen preventive work and ensure that local preparedness resources pull together to a greater extent when needed.

In the event of major incidents, municipalities must quickly be offered support to enable them to handle such incidents in the best possible manner. The Government will establish a reinforcement scheme for municipalities exercising crisis management in the areas of psychosocial support, communication and support for staff functions in crisis coordination. The Government will also consider establishing a cyber security reserve in which the authorities and business sector cooperate in the event of major crises and incidents that require extra capacity and expertise.

The Government has allocated funding for a pilot project to increase resilience and preparedness in Finnmark. The Government will consider measures to further strengthen resilience in Troms and Finnmark counties and in other strategically important geographical areas.

Figure 1.1 The quick clay landslide at Gjerdrum

Photo: Stian Olberg/DSB.

Strengthen the presence of emergency services throughout Norway

Society’s resilience depends on the emergency services being present where incidents occur. Citizens should have the assurance that they will be taken care of in emergency situations, and should experience that larger society provides resources in critical situations. Given that Norway is a long country with settlements scattered across great distances, this will have an impact on how we organise our services. Local knowledge and rapid response will always be key to handling incidents.

Reintroduce the obligation to build emergency shelters and develop a new protection concept

The war in Ukraine illustrates the need for emergency shelters during war. From 1998, developers were exempted from the obligation to build shelters in new buildings. The government will now revoke the exemption. At the same time, the Government aims to introduce a new protection concept and will soon submit a proposal for public consultation.

Strengthen the business sector throughout Norway

Society’s resilience depends on having a diverse business sector throughout the country. The private sector owns, operates and develops critical infrastructure, and plays a crucial role in both our capability to ensure the continuity of critical societal functions and for civilian support to military operations. The business sector also has a number of tangible resources, such as personnel and mechanical equipment, which can be of great use in handling incidents.

Increase funding for voluntary organisations

The voluntary organisations in the rescue service are a key part of basic preparedness in Norway. The Government will take steps to increase funding, by up to NOK 100 million, for volunteers in the rescue service, scaling the funding up over eight years. In collaboration with the voluntary organisations, an assessment will be made of how the funding can be allocated in the best way possible. The Government has proposed, and the Storting has approved, an increase of NOK 6 million in grants to voluntary organisations in the rescue service in 2025.

Make better use of society’s collective resources in prevention and crisis management, including involving the business and voluntary sectors in preparedness work at the local, regional and national levels

All civilian sectors must be prepared for serious crises and war. Better coordination and prioritisation of resources between the public, business and voluntary sectors is required to ensure good information sharing and to optimise efficient and flexible utilisation of society’s collective resources. The Government will endeavour to ensure that all parts of civil society cooperate more closely, share more information and conduct more training exercises together.

Establish a new council structure that involves the private and voluntary sectors

The Government will establish a uniform council structure at national, regional and local level to improve the coordination of emergency preparedness work.

At the national level, emergency preparedness councils will be established in critical areas of society that do not have such councils at present. The councils will be chaired by the responsible ministry, and other public agencies, businesses and voluntary organisations will participate. Among other things, the councils will contribute to the annual preparation of vulnerability and status assessments within the critical areas of society. This will give the responsible ministries the best possible basis for proposing measures to strengthen preparedness. The Ministry of Justice and Public Security will prepare an overall assessment across all areas of society as a basis for the Government’s priorities.

At the local level, the Government will introduce an obligation for all municipalities to have or be affiliated with a municipal emergency preparedness council. The councils should include local emergency preparedness actors such as voluntary organisations and the private sector.

Establish a long-term plan for civil preparedness

The Government will establish a long-term plan for civil preparedness, and work to this end is scheduled to start in 2025. The purpose of the long-term plan will be to strengthen civil preparedness, ensure continuity, coordination, cross-sectoral work and a long-term approach. The long-term plan will enhance the link between risk assessments and political measures. The new council structure for preparedness planning and status assessments in civilian sectors will give the Government a good basis for preparing the long-term plan, which will be developed over time.

Submit a proposal for a new act on fundamental security for undertakings that are important for society

The Government will submit a proposal for a new act on fundamental security for undertakings that are important for society. The act is linked to the preparation for the national implementation of the directives on the security of networks and information systems (NIS2 Directive) and the critical entities resilience directive (CER Directive). The new act will set common requirements for fundamental security for undertakings that are important to the functioning of society, in peace, crisis and war.

Strengthen our shared situational awareness against hybrid threats

In order to prevent, resist and handle hybrid threats, it is crucial that, as a society, we understand what we are facing and the assets at our disposal. The National Intelligence and Security Centre (NESS) consists of the Norwegian Police Security Service, the Norwegian Intelligence Service, the Norwegian National Security Authority and the police. The centre works to strengthen Norway’s capability to identify hybrid threats and ensure good decision-making support for the authorities. The Ministry of Justice and Public Security and the Ministry of Defence are now further developing NESS to establish a national situational picture of hybrid threats, and to strengthen the cross-sectoral work required to identify, understand, counter and handle hybrid activities.

Conduct more training exercises together with allies, industry and voluntary organisations

If society is to function during crises and war, we must train more. Such training exercises make it easier for society’s collective resources to pull together and increase our capability to deal with serious incidents.

The Government will prepare a strategic framework for national training exercises in civilian sectors and a multi-year plan for national training. The Government will take steps to ensure more training exercises are conducted and that more actors train together. The goal is a more systematic approach and better coordination of training exercises across civilian sectors and together with military exercises.

Develop a national security strategy

The rapidly changing security situation means we need more comprehensive and long-term management of efforts to safeguard national security interests. The Government has therefore initiated work on a national security strategy. The strategy will provide a comprehensive overview of foreign, security, defence and preparedness policy, based on our national security. The strategy will be presented before summer 2025.

Strengthen cyber resilience and national control over critical infrastructure and strategically important undertakings, natural resources, property and assets

Key elements of Norwegian infrastructure are currently owned by private companies. Certain sectors are particularly exposed to changes in the security policy situation. The Government will strengthen cyber resilience and national control over critical infrastructure, natural resources, property and strategically important undertakings. This must be done in a way that ensures the necessary predictability for businesses and maintains Norway’s open economy.

Propose a new act on the control of foreign investments in strategically important sectors

In response to the new security policy reality, several changes have already been made to the Security Act, including tightening the rules for ownership control. National security interests may also impact undertakings that are not covered by the Security Act. In order to further develop the current system for handling foreign investments that potentially threaten security, the Government will present a new act on the control of foreign investments.

The Government has recently established the Directorate for Export Control and Sanctions (DEKSA). Among other things, DEKSA will be responsible for issuing permits, guidance and executive control of exports of defence materiel, dual-use items, technology, services and knowledge.

Improve the overview of the actual owners of properties and establish a system for the approval of buyers of certain properties

The overview of actual owners of real estate is currently inadequate. Nor do we have expedient policy instruments to control the purchase of properties that may have security implications because they are located close to critical infrastructure such as ports, defence facilities or power supplies. The Government will investigate implementing statutory ownership registration to determine who owns real estate, and will propose necessary amendments to ensure prior authorisation to purchase certain properties, for example in the vicinity of military installations or other critical national infrastructure.

Strengthen maritime security and security around port infrastructure

With one of the world’s longest coastlines, we are particularly vulnerable to maritime covert intelligence activity. To strengthen the work on maritime security, the Government has initiated close cooperation between the civil and military authorities, and with the private sector. This work will be further stepped up. The Government has adopted the emergency preparedness regulations for ports (havneberedskapsforskriften), which, among other things, will ensure that military forces have access to relevant ports in a state of war. The Government has also adopted new regulations on entry into territorial waters (anløpsforskrift) to improve control of foreign vessels entering Norwegian territorial waters and, together with our allied neighbours, is helping to ensure that maritime areas are not exploited in connection with sanction evasion, environmentally harmful conduct and other risky activities at sea, such as threats of sabotage, also linked to vessels in what is known as the ‘shadow fleet’, through increased surveillance, cooperation, presence and control in our maritime areas.

Step up work on critical underwater infrastructure

As a result of Russia’s war against Ukraine, the Government has implemented several measures to protect critical underwater infrastructure. In 2024, NATO established a centre for the protection of underwater infrastructure on the initiative of Prime Minister Støre and German Chancellor Scholz. This work will be expanded. The Government seeks close international cooperation to protect critical infrastructure. Close cooperation between private and public actors, across sectors, is also essential to protect critical underwater infrastructure. Protecting critical underwater infrastructure is a priority for the Government.

Establish a personnel clearance system fit for the future

The better cyber security systems become, the more we must expect that malicious actors will attempt to gain access to critical national objects and infrastructure via individuals. As the number of organisations that handle critical national information increases, so does the need for security clearance for personnel. At the same time, organisations need access to critical expertise and personnel. The Government will strive to ensure that we have a personnel clearance system that is fit for the future.

Be clearer about the trade-offs between economy, openness and security

In the current situation, foreign state actors use economic means to gain influence, control and access to sensitive information. National security issues therefore affect not only public authorities, but also businesses, academia and local authorities. As a society, we need to make it clearer that important considerations such as openness and commercial interests must be weighed against national security considerations. The trade-offs can be demanding, and the Government will therefore take steps to establish a clearer dialogue with businesses, academia and local authorities.

Increased expertise in cyber security

Access to cyber security expertise is a prerequisite for developing cyber resilience. The Government will consider measures to increase the number of people with the necessary cyber security expertise and ensure the most effective use of the expertise available.

Investigate establishing a national cyber security reserve with the private sector

The business sector has important capacities, knowledge, expertise and innovative power in the cyber security field. The Government will soon begin work on a national cyber security reserve consisting of relevant authorities and business communities.

Establish closer international cyber cooperation

Cyber incidents often occur across national borders. National capacities for detection and incident management must be supplemented by international cooperation. The Government will strengthen international cooperation by participating in a Nordic-Baltic cyber security partnership.

Strengthen the population’s resilience and maintain a high level of trust in society

A comprehensive strengthening of national preparedness requires the participation of the entire population. Each and every one of us is responsible for following the self-preparedness advice (see Section 6.1.3) and preparing for situations where normal societal functions do not work.

Strengthen the population’s resilience to disinformation

The Government has expanded the self-preparedness advice to the population to include advice on what the individual can do to identify misinformation and disinformation. Our primary defence is counter-information and a free and open debate. In the spring of 2025, the Government will present a strategy to strengthen the population’s resilience to disinformation. The Government will, in consultation with the media industry, assess possible measures to improve people’s ability to scrutinise sources and resist disinformation.

Strengthen the Civil Defence

The Norwegian Civil Defence is Norway’s most important civil reinforcement resource. It can support the emergency services in the event of major accidents and natural disasters and protect civilians in the event of military action. The Government wishes to increase the number of conscripts in the Norwegian Civil Defence from 8,000 to 12,000 over an eight-year period. The need to further develop the Civil Defence’s expertise and capacities will be investigated at the same time.

Criminalise influence operations

When influence operations are of such a serious nature that significant societal interests are at stake, society must be protected by criminal law. Influence operations can undermine trust in society. In 2024, the Government proposed a bill criminalising the most serious influence operations. The act has entered into force.

Safeguard preparedness and security considerations in public procurement to a greater extent

Every year, the public sector procures goods, services and construction work for significant sums. The Government will investigate the possibility of implementing security and preparedness requirements in public procurement in order to safeguard preparedness and national security interests. Good guidance on security and preparedness in public procurement is also important, to enable clients to use the scope provided for in the procurement regulations and ensure that the right requirements are set in the procurements.

Strengthen security of supply, including food security

Stable access to goods and services is crucial for society’s resilience and civil society’s support to military efforts to defend the country. Supply line failures can affect the ability to maintain continuity in critical areas of society, civilian capability to support military efforts, and the individual community’s and individual citizen’s ability to take care of themselves during crises. The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have highlighted vulnerabilities in global supply lines. The Government will also continue its efforts to strengthen Norway’s self-sufficiency, including in relation to food.

Step up work on security of supply

The Government has decided to assign the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries responsibility for coordinating work on security of supply across sectors, relating to goods and services within the scope of the Act on Business and Industry Preparedness. In connection with the work on strengthening security of supply, the Government will investigate the need for, and design of, an underlying and sector-neutral apparatus in the area of security of supply.

Strengthen national food security

Sufficient and safe food is a prerequisite for any society, and, since taking office, the Government has prioritised stepping up Norwegian food production. Maintaining agriculture throughout the country is crucial to Norway’s preparedness. Increased self-sufficiency, stockpiling grain and strong soil protection increase preparedness and security. The Government will conduct a risk, preparedness and vulnerability analysis of the Norwegian food supply.

Ensure closer cooperation between the civilian sectors and the defence sector

Handling situations at the high end of the crisis spectrum requires that society’s collective resources pull together. Resources and expertise in civilian sectors that are able to support the Norwegian Armed Forces and allied forces strengthen overall defence capability. The Government wishes to strengthen civil protection measures and facilitate civil society’s ability to support military efforts in the event of war or conflict.

New regulation to ensure access to and prioritisation of the civilian workforce in security policy crises and war

In a situation where the realm is at war or war is threatening or the independence or security of the realm is in danger, the civilian workforce will be required to support the country’s defence, including road, rail, sea and air transport. The Government has proposed a new act relating to the preparedness of the civilian workforce. The act will ensure access to and prioritisation of civilian labour in security policy crises and war. The proposal seeks to pre-establish key issues and considerations related to civilian workforce preparedness, and will provide a better basis for planning, carrying out training exercises and making necessary preparations in peacetime.

Develop a common basis for civil preparedness planning

As announced in the long-term plan for the defence sector, the Government will ensure that the need for civilian support for military efforts within the framework of total defence is communicated more systematically by the defence sector to civilian sectors than is currently the case. The Government will coordinate the civilian sectors’ follow-up of the military needs. The Directorate for Civil Protection prepares crisis scenarios, including natural events, supply failures and disease outbreaks. The Government will implement a more binding follow-up of crisis scenarios.

Update the planning framework for wartime relocation of citizens

The Government has initiated work on updating the plan for wartime relocation of citizens. The current planning framework has not been updated for decades.

Strengthen civilian capacity to support allied military efforts within the framework of NATO and through enhanced Nordic and European preparedness cooperation

The capacity to support allied forces is crucial to their ability to assist Norway in crisis and war. The Government will strengthen Norway’s role as a host and transit nation for allied forces.

Follow up NATO’s new host nation support concept

To be able to quickly receive and host allied forces, civil society, as part of our total defence, must be prepared. Civil society must, among other things, have an organised infrastructure and planned deliveries of services and goods to allied forces. NATO is developing a new concept for host nation support. The Government will follow up the new concept at the national level.

Strengthen civil preparedness cooperation in the Nordic countries

To increase our overall capability to provide effective civilian support to military efforts in war, the Government will strengthen civil preparedness cooperation with Finland and Sweden. As a result of Swedish and Finnish membership of NATO, the need to transport materials and personnel across the borders between the three countries has increased. The Government will continue its efforts to increase military mobility, including by developing a strategic corridor for military mobility through northern Norway, northern Sweden and northern Finland.

2 A broad approach to preparedness and total defence

This white paper emphasises resilience and total defence in situations at the high end of the crisis spectrum, i.e. our capability to prevent and handle hybrid threats, security policy crises, armed conflict and, in the worst case, war. These situations arise as a result of deliberate actions by one or more malicious actors with the intention of harming us. The perspective in the white paper is motivated by the security policy situation.

However, the work on resilience and preparedness is of a much broader scope. Our broad approach to preparedness is geared to being able to prevent and handle a wide spectrum of different incidents, all of which can have serious consequences.1 These could be serious natural events such as the extreme weather event ‘Hans’ in 2023 (see Box 2.1) and the quick clay landslide at Gjerdrum in 2020 (see Box 2.2), accidents such as that involving the cruise ship ‘Viking Sky’ off Hustadsvika in 2019 (see Box 2.3), or deliberate actions that have serious consequences, such as a cyberattack. Strengthening the broad approach to preparedness ensures basic preparedness in society. The broad approach to preparedness, including good coordination, is also important for our ability to deal with incidents at the high end of the crisis spectrum, because the same actors and resources are used to handle the most serious incidents.

Textbox 2.1 The extreme weather event ‘Hans’

On 7 August 2023, the extreme weather event Hans hit southern Norway, causing landslides, debris floods and flooding. An unusually severe weather front brought very heavy rainfall on top of an already high groundwater level after heavy rain during late summer and early autumn, causing extensive damage to infrastructure and property. The consequences continued for weeks after the extreme weather had passed.

The evaluation of the incident management1 concluded that the extreme weather event Hans was, on the whole, well managed. The early, clear notification of the various actors involved was vital to expedient and coordinated management of the event. The various central, regional and local services’ resources pulled together, and actors such as the Home Guard, Norwegian Civil Defence, voluntary organisations (such as the Red Cross, Norwegian People’s Aid and Women’s Public Health Association), as well as private actors and businesses, played an important role in handling the incident.

The evaluation made several recommendations to further step up preparedness. These included the need for better guidance to municipalities in their systematic work on flood and landslide protection, for municipalities to carry out more training exercises based on their own needs and analyses, and for the Norwegian Meteorological Institute and the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate to provide earlier, clearer and more consequence-based extreme weather warnings, so that relevant actors have even more time to prepare.

The evaluation has contributed to a good knowledge base for managing extreme weather events in future. Actors affected by the recommendations are preparing plans for compliance.

1 Evaluering av ekstremværet Hans – forebygging, beredskap og håndtering (Evaluation of the extreme weather event Hans – prevention, preparation and management – in Norwegian only). Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection, 2024.

Textbox 2.2 The quick clay landslide at Gjerdrum

On 30 December 2020, the village of Ask in Gjerdrum municipality was suddenly and brutally hit by an extensive quick clay landslide. Ten people lost their lives, and many others were rescued from the landslide area during a demanding rescue operation. Many people had to be evacuated. The management of the incident was subsequently evaluated. The evaluation report1 concluded that there was no evidence that more lives could have been saved during the rescue operation, and that the immediate evacuation of residents and the efforts of the organised rescue service saved many lives. A large number of organisations took part in the rescue operation, and voluntary organisations also played a major role in this incident. The evaluation did, however, identify a number of learning and improvement points related to, among other things, the management of the rescue effort in Ask, civil-military cooperation, coordination of actors who participated in the handling of the incident, safeguarding of vulnerable groups and crisis management related to critical societal functions and services. The work on following up the learning points is ongoing.

1 Redningsaksjonen og den akutte krisehåndteringen under kvikkleireskredet på Gjerdrum (Rescue operation and emergency crisis management during the quick clay landslide in Gjerdrum – in Norwegian only) Report to the Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Joint Rescue Coordination Centre, 1 June 2021.

Textbox 2.3 The ‘Viking Sky’ cruise ship incident

On 23 March 2019, the cruise ship Viking Sky suffered engine failure and distress at sea at Hustadvika between Kristiansund and Molde in Norway. The ship was very close to running aground, which could have had disastrous consequences. An extensive rescue operation was launched and almost 500 passengers were evacuated by helicopter and transported to a reception centre on land.

The evaluation of the incident1 concludes that the rescue operation was successful, with excellent efforts and good cooperation between the actors involved. A public committee was subsequently appointed to assess the emergency preparedness challenges associated with increasing cruise traffic in Norwegian waters. A public report was submitted to the Minister of Justice and Public Security in 2022 (Norwegian Official Report (NOU) 2022: 1). The report made a number of recommendations with an emphasis on risk-reduction measures.

Learning points and recommendations in both the evaluation and the report affect several ministries’ sectoral responsibilities and many subordinate agencies. Several of the recommendations have been followed up through ongoing emergency preparedness work in a number of organisations. Among other things, the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre has been awarded more resources to step up its capacity to lead and coordinate complex rescue operations at sea, and planning work has been initiated for mass evacuations. The reviews also show the breadth of actors involved in the management of such incidents. In addition to public agencies at central and regional level and in the affected municipalities, a number of voluntary organisations and many private organisations participated in the rescue operation.

1 Assessment of the Viking Sky incident. Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection, 31 January 2020.

Good basic preparedness helps ensure that incidents can be handled locally with as little delay as possible. Basic preparedness is also important for credible deterrence and reassurance, by demonstrating that civil society, both nationally and locally, can support military efforts and maintain critical functions as far as possible. For example, fire and rescue services, the emergency services, the police and the health and care services must fulfil their core tasks for the public, while also providing support to military efforts.

The Government shares the Total Preparedness Commission’s view that the population, municipalities, emergency services, the publicly organised rescue service and voluntary rescue and emergency response organisations are the pillars of basic preparedness in Norway. The private sector, broad organisational sector and voluntary sector are also important for our preparedness and the resilience of society.

The broad preparedness approach also includes specific measures in selected areas. One example is the Merkur programme, in which the Government supports local shops in areas with small markets and long distances to the next shop. These shops can be of great importance to local communities in the event of, for example, major natural disasters (see Box 2.4). They could also be of great importance to the local community in the event of security policy crises or war.

Textbox 2.4 The local shop’s important role during the extreme weather event ‘Hans’

The local shop came to the rescue of tourists and locals alike when the extreme weather event Hans ravaged Hallingdal. Snarkjøp Samhald Landhandel in the village of Leveld served as both a supply hub and a base when emergency networks, telephony, internet and other infrastructure failed in other parts of Ål municipality. The contingency solution in the digital shop meant that operations could continue. Customers were also able to use the shop’s network to communicate with the outside world.

The four principles of responsibility, proximity, similarity and collaboration (see Box 2.5) form a common foundation for preparedness work. The Government considers it important that actors who fulfil important roles in preparedness work are mindful of the purpose of the preparedness principles, which entail, among other things, that relevant actors have sufficient knowledge of each other’s tasks and responsibilities. This is paramount for the best possible coordination and utilisation of society’s collective preparedness resources.

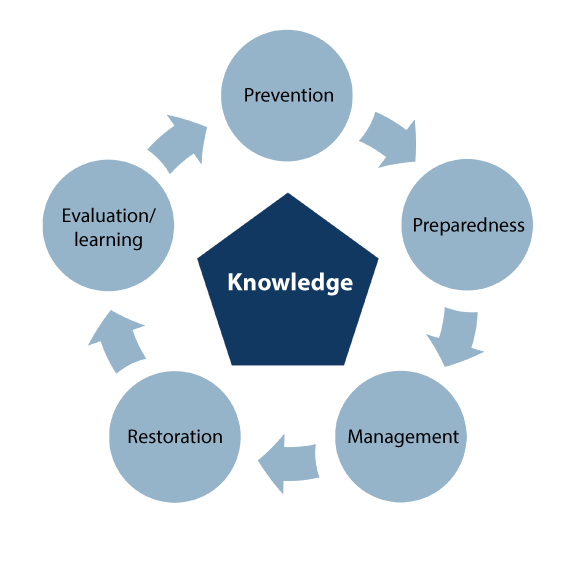

Furthermore, efforts to further develop broad preparedness must be systematic and should be seen as a continuous chain, see Figure 2.1. The different parts of the work are interconnected, and they impact each other. Systematic preparedness work requires active efforts in all parts of the figure, and necessary cooperation with relevant actors, including the private and voluntary sectors.

Textbox 2.5 The four basic principles for public security work

-

The principle of responsibility means that the organisation responsible for a given area in a normal situation is also responsible for the necessary emergency preparation and for handling extraordinary incidents in the area. The responsible body must define acceptable risk.

-

The principle of similarity means that the organisation in operation during a crisis should, in principle, be as similar as possible to the day-to-day organisation.

-

The principle of proximity means that crises should be handled at the lowest possible organisational level.

-

The principle of collaboration means that authorities, organisations or agencies have an independent responsibility to ensure the best possible collaboration with relevant actors and organisations in the work on prevention, preparedness and crisis management.

Figure 2.1 The work on security and preparedness – an ongoing improvement process

Some incidents require regional and national assistance. National reinforcement resources are mobilised when incidents require more resources or different expertise than that available in local communities. Key examples of national reinforcement resources are the Norwegian Civil Defence and the Home Guard, as well as other resources in various sectors, such as the resources of the national police emergency response centre and the national forest fire helicopter service. Good coordination is important for management capability. It is therefore important that preparedness actors regularly practise managing different types of incidents.

Voluntary rescue and emergency response organisations are crucial to preparedness. They play a key role in search operations on land, in forests and in the mountains, and in incidents at sea. They also provide first aid assistance. The organisations have personnel with good fundamental expertise. They also have specialist expertise in communications, rescue in steep, difficult terrain and caves, and searches with dogs, small aircraft and rescue boats. The number of assignments for volunteers is likely to increase in the years to come, and the voluntary sector will continue to play an important role in emergency response work. The presence of voluntary organisations throughout the country is therefore an important element in Norway’s preparedness.

2.1 The Government’s strengthening of the broad approach to preparedness

Regardless of where you live in Norway, it is crucial that emergency response organisations are present in local communities and that they have the capability to provide rapid assistance. After major incidents, good systems are needed to follow up those affected. In recent years, the Government has strengthened its broad approach to preparedness, as a means of helping to safeguard the lives and health of citizens during various types of incidents.

The Joint Rescue Coordination Centre and the rescue services

The rescue services fulfil their social responsibility during peacetime, crises, armed conflict and war. The number of rescue operations has risen steadily in recent years. The pace of rescue operations has also increased, and rescue operations have become more complex. More and more people are being rescued, but this has meant a high workload for the staff at the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC) for several years. The Government has increased basic staffing at the JRCC offices at Sola and Bodø by employing more rescue leaders. JRCC rescue leaders manage the use of rescue helicopters in connection with search and rescue missions. Increasing basic staffing at Sola and Bodø has helped to ensure that the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre is well-equipped to manage more rescue operations, address the risks associated with climate change and meet the challenges linked to increased maritime traffic in the High North. Increasing the number of rescue leaders will also strengthen cooperation in the Norwegian rescue service.

The Joint Rescue Coordination Centre can further strengthen and rationalise its efforts to communicate knowledge to emergency response actors by systematising and developing their unique insight in leading rescue operations at sea and on land, in cooperation between public and private, civil and military emergency response actors. The purpose of organising this knowledge more expediently is to ensure that rescue response in Norway is adapted to climate change and changes in demographics. The aim is also for the service to adopt new technology more quickly than it does today to ensure public resources are used correctly in life-saving efforts.

The JRCC plays a key role in the development of procedures, manuals and ICT solutions. Though a development project that has run over several years, it has helped to develop an app that will be used to plan and carry out searches for missing persons on land. The tool will streamline the execution of search and rescue missions by utilising available technologies and exchanging information and data between actors in the rescue service in Norway. Since mid-June 2024, the tool has been tested in a pilot study in the Southwest Police District, and is scheduled to be rolled out nationwide in 2025.

The management of the rescue helicopter service was transferred from the Ministry of Justice and Public Security to the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre on 1 January 2024. The Joint Rescue Coordination Centre is now responsible for ensuring appropriate cooperation and utilisation of the rescue helicopters, and takes a more comprehensive approach to the development of the Norwegian rescue helicopter service.

The rescue helicopter service is a dedicated state resource in the rescue service. It consists of the Air Force’s 330 Squadron, as well as the civil helicopters under the authority of the Governor of Svalbard and the civil rescue helicopter base in Tromsø, which CHC Helikopterservice operates. The Air Force has operated from six permanent bases: Banak, Bodø, Ørland, Rygge, Sola and Florø. SAR Queen was commissioned at its first base at Sola on 1 September 2020. This marked the start of a new era for the rescue service in Norway, with improved range, speed and medical capacity compared with the old Sea King helicopters. On 1 October 2024, SAR Queen was put into operation at the Florø base as the sixth and last base operated by the Norwegian Armed Forces. The new rescue helicopters increase the safety of people at sea, along the coast and in remote areas of Norway. The helicopters are a significant boost to the rescue service and air ambulance capacity, and will help to improve patient transport.

The Government issues grants to voluntary organisations in the rescue service. These organisations are unique resources that work closely with the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre. Grant management for the rescue helicopter service was transferred from the Ministry of Justice and Public Security to the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre on 1 January 2024. See also Section 5.4.1.

Figure 2.2 SAR Queen

Photo: Fabian Helmersen/Norwegian Armed Forces.

The police

The Government wants thriving and safe communities throughout Norway. The role of the police in society is to protect, maintain peace, order and security, prevent crime, uncover and stop crime and help citizens in given situations. The police also provide assistance to others when needed.

The police fulfil their social mission in close cooperation with other sections of society, from government agencies and the business sector to individual citizens. The police play a key role in most crises, and it is crucial that they also contribute actively in cases where they assist others. Like the Total Preparedness Commission, the Government believes that the use of police capacity and resources must be seen in the context of other preparedness resources in the civil, private and voluntary sectors, in addition to defence resources. This is particularly true in areas where police expertise or police authority is not essential.

The Government has presented the action plan Trygghet i hverdagen (Safe everyday lives – in Norwegian only), which sets out a clear direction for a police force that is present in the communities across Norway and helps to create a sense of security and prevent crime where people live. Local knowledge and presence are crucial to handling incidents. This also sets an important framework for the organisation of the police force, and is relevant for achieving police presence in both cities and rural areas. For example, one measure in the action plan is to run a pilot decentralised police training programme in Alta from autumn 2025. This will give more police trainees a local affiliation, and contribute to more stability and less turnover in the police force in our northernmost county. Experience shows that local affiliation increases the likelihood of staying in a job and an area for a longer period of time. The programme could also attract applicants from other parts of the country, which would be a positive development.

The national preparedness resources assist the country’s police districts and specialist agencies in connection with incidents of particular complexity and risk. The capabilities and capacities of the national preparedness resources augment the police’s ability to prevent and tackle terrorist incidents and organised and other serious crime. The resources are co-located at the police’s national emergency response centre. The establishment of the police’s national emergency response centre gave some of the response personnel (IP3) in all police districts the opportunity to train with the national resources at the centre. As a result, the local response personnel in each police district will be better equipped to fulfil their duties. See also Section 5.4.7.

Health and care services

Health and care services are part of basic preparedness. The purpose of health preparedness is to protect life and health, and to help ensure that the population can receive the necessary health care and social services in the event of crises and disasters, in times of peace and war. The Government’s Report No 5 to the Storting (2023–2024) A Resilient Health Emergency Preparedness – From Pandemic to War in Europe, and the Storting’s approval, cf. Recommendation No 220 to the Storting (2023–2024), provides political and strategic direction for Norwegian health preparedness. The report presents four main initiatives:

-

The Government will step up Norway’s international cooperation on health preparedness. The COVID-19 pandemic showed how vulnerable we are on our own. Most importantly, an agreement must be reached on participation in the strengthened EU health crisis preparedness programme.

-

The Government will work to make the health and care services more adaptable and flexible. This requires prioritisation, an overview of personnel resources and the redeployment and mobilisation of resources. In the National Health and Care Coordination Plan 2024–2027, the Government has set out its policy for recruiting, retaining and developing professionals for the health and care services we share. The focus areas to ensure access to personnel are i) working environment and working conditions, ii) task sharing and efficient organisation, iii) recruitment, qualification and skills development. Several specific initiatives have been implemented to address this.

-

The Government will establish a new model for work on health preparedness. The model will clarify roles and responsibilities in the health sector and help ensure even greater priority is given to security and preparedness work in the sector.

-

The Government is strengthening cross-sectoral collaboration and cooperation with the voluntary and business sectors. We must utilise society’s collective resources better.

The new health preparedness model involves the establishment of structures that will strengthen the ministry, agencies and organisations in their day-to-day follow-up of risk and vulnerability analyses, training exercises, coordination of plans and other public security work and in crisis management in the health sector. The model involves the establishment of a Health Preparedness Council with representation from all sectors, to be chaired by the Ministry of Health and Care Services, and six committees at agency level to work on risk areas and cross-sectoral collaboration. An expert advisory committee for health crises will also be established to ensure a better knowledge base for handling crises that affect society as a whole, which requires comprehensive interdisciplinary assessments. Roles and responsibilities are outlined in the National Health Preparedness Plan, which is currently under revision. This will be the fourth edition of the plan. The structural changes in health preparedness that follow from Report No 5 to the Storting (2023–2024) is an important reason for updating the plan. Roles, responsibilities and structures will be emphasised in the updated version. See also Section 5.4.9.

The fire and rescue service

The fire and rescue service is key to basic preparedness in Norway and an important element in our total defence. Municipalities are responsible for the establishment and operation of a fire and rescue service. The municipalities can choose whether they want to operate the fire and rescue service themselves or cooperate with other municipalities on a joint fire and rescue service or joint management. As of October 2024, there were 194 fire and rescue services in Norway. The fire and rescue service employs a total of approximately 12,000 people, comprising 4,200 full-time employees and 7,800 part-time employees. There are more than 600 fire stations in Norway. Approximately 85% of the population live within a 10-minute drive of a fire station.

On 22 March 2024, the Government presented Report No 16 (2023–2024) Brann- og redningsvesenet – Nærhet, lokalkunnskap og rask respons i hele landet (Fire and Rescue Service – Proximity, local knowledge and rapid response throughout Norway – in Norwegian only) to the Storting, which has approved the report, cf. Recommendation No 413 to the Storting (2023–2024). The report sets out a fire and rescue service that is able to handle current and future challenges, both within its own sectoral responsibility and in collaboration with other emergency services and emergency response organisations. The fire and rescue service will continue to be a municipal responsibility and a nationwide organisation. Their municipal organisation ensures proximity to residents, local knowledge and rapid assistance when people need help, both in cities and in rural areas. The Government intends to build on the strengths of the fire and rescue service and keep up the excellent work performed every day by full-time and part-time personnel.

The fire and rescue services are organised and dimensioned to handle local incidents. Situations may arise that require specialist knowledge and equipment that not all fire and rescue services have access to. Events such as quick clay landslides, extreme weather, major fires in forests or built-up areas are relatively rare, but can occur in areas of the country where there are no resources to effectively deal with such events. Many municipalities have entered into local and regional cooperation agreements to meet these challenges. The Government believes that the municipalities themselves are best placed to assess whether establishing cooperation with others is necessary and appropriate. Regional cooperation should be based on risk and vulnerability analyses and designed to ensure the best possible access to specialist expertise in all parts of the country. See also Section 5.4.8.

Voluntary organisations

Voluntary organisations are an indispensable part of Norway’s preparedness system. In Norway, they enjoy a high level of trust and also contribute to general welfare and confidence in society. Norwegian voluntary organisations have a long tradition of providing assistance in connection with various public tasks, and can mobilise, channel and organise both grassroots involvement and specialist assignments in an effective manner. The organisations are characterised by short response times, good local knowledge and flexibility. In many cases, voluntary organisations can also contribute knowledge about groups that often fall outside crisis and preparedness thinking, or that are difficult to reach through official channels. Further consideration should be given to how voluntary organisations can be well integrated into various coordination bodies at the national, regional and local level to ensure timely and efficient use of resources across the entire crisis spectrum. Closer and more formalised collaboration arenas between voluntary organisations and government agencies are discussed in more detail in Sections 3.1 and 5.1.1.

Figure 2.3 During the pandemic, the Red Cross assisted in connection with vaccinations

Photo: Aleksander Båtnes/Red Cross.

The Government is of the opinion that a state and municipal volunteering policy must be developed in the area of preparedness. This will help to ensure greater involvement of voluntary organisations. The Directorate for Civil Protection’s municipal surveys show that there are still many municipalities that do not cooperate with voluntary organisations in their work on preparedness planning, risk and vulnerability analyses, training exercises and crisis management. Although entering into emergency response agreements with municipalities does not in itself guarantee good collaboration, the Government believes that such agreements can help to clarify roles, needs and expectations between municipalities and voluntary organisations. Establishing meeting places will also be important to further develop collaboration. The Government believes that increased collaboration between municipalities and voluntary organisations will be particularly relevant because both have good knowledge of local emergency preparedness and attach great importance to it.

Voluntary organisations that are involved in the rescue services in Norway have access to the emergency alert system Nødnett. This critical network provides effective radio communication between the police, fire service, health services, Norwegian Civil Defence and voluntary organisations during accidents, crises and other incidents. Voluntary organisations’ expenses for their current Nødnett terminals are covered under the grant scheme for volunteers in the rescue services. In 2022, NOK 10 million was allocated to the voluntary organisations in the rescue services to cover annual operating and subscription expenses for 2,000 new Nødnett terminals. See also Section 5.4.2.

Textbox 2.6 Voluntary organisations with emergency response agreements with public authorities

Voluntary organisations with emergency response agreements with public authorities in Norway. These agreements ensure that volunteers can contribute effectively in crisis situations and strengthen Norway’s preparedness.

For example, many municipalities have agreements with organisations such as the Red Cross, Norwegian People’s Aid, the Norwegian Women’s Health Association and the Norwegian Society for Sea Rescue. Agreements can include financial support, access to equipment and coordination of efforts in emergency situations. The Norwegian Radio Relay League has radio enthusiasts who can be used by the rescue services and in connection with disaster and crisis preparedness, and can organise preparedness for the authorities through contact with central and local police authorities, counties and municipalities. The services are divided into three areas: crisis communication, rescue and other communication assignments. Such agreements are essential to ensure a rapid and coordinated response to crises, and help ensure the effective utilisation of both public and voluntary organisations’ resources. The agreements contribute to continuity and systematisation in preparedness work.

Textbox 2.7 FORF

Frivillige Organisasjoners Redningsfaglige Forum (FORF) is a cooperation body for voluntary rescue organisations in Norway. The main purpose of FORF is to improve the quality of the Norwegian rescue service and serve as a link between the voluntary organisations and public authorities. It is generally the organisations in FORF that are called out on search and rescue assignments. FORF works to

-

collect and promote member organisations’ views and needs in relation to the authorities and other stakeholders.

-

ensure good cooperation between the member organisations and rescue authorities.

-

strengthen total preparedness by coordinating the efforts of the voluntary organisations.

Eight organisations are members of FORF:

-

Red Cross Rescue Corps

-

Norwegian People’s Aid rescue service and first aid

-

Norwegian Society for Sea Rescue

-

Norwegian Search and Rescue Dogs

-

Norwegian Radio Relay League

-

Scout Movement Emergency Response Groups

-

Norwegian Speleological Society

-

Norwegian Air Sports’ Federation air service

The Norwegian Civil Defence

The Norwegian Civil Defence is a state emergency resource whose primary task is to protect the population during war. In peacetime, it is also the state’s most important civilian reinforcement resource for emergency and preparedness actors and is trained and equipped to support the police, fire service and medical personnel in the event of major accidents and natural disasters. The Civil Defence is therefore an important actor across the entire crisis spectrum (see also Section 5.4.6).

In peacetime, the Civil Defence consists of 8,000 conscripts divided into 20 civil defence districts. It is very important to retain the decentralised structure and organisation of the Civil Defence, to ensure local knowledge, short response times and local affiliation. The Civil Defence may also, by decision of the responsible authority, mobilise a war reserve of additional conscripts.

The Civil Defence, which is subordinate to the Directorate for Civil Protection is responsible for a number of civil protection measures. These are described in more detail in Section 6.1. The Civil Defence is organised with local, regional and national task forces consisting of conscripts and officers. The decentralised structure, with advance storage of equipment and materials throughout the country, facilitates local knowledge and good interaction with key collaborating actors such as the municipalities, county governors, the police and the Home Guard.

Figure 2.4 The Norwegian Civil Defence

Photo: Arild Ødegaard/Directorate for Civil Protection.

The municipalities

The municipalities are important for basic preparedness throughout the country, and they have extensive responsibility for ensuring the safety and security of the population. The municipalities must be prepared to handle undesirable incidents, and they must therefore work systematically and comprehensively on public security across sectors in the municipality. It is also the responsibility of the municipalities to, as far as possible, prevent incidents from happening. Climate change demands that we adapt to a climate with a greater frequency of extreme weather events. It is therefore important that our legislation does not act as an obstacle to effective prevention of various incidents.

Norway has a municipal structure that ensures residents have easy access to public services and local elected representatives, and which utilises residents’ local knowledge of site-specific needs and challenges in service development and administration. Settlement throughout the country is crucial to maintaining a resilient, vibrant and sustainable society (see Figure 2.5). A decentralised settlement pattern also helps to ensure that necessary services and resources are available throughout the country. This makes it easier to protect people and communities against various threats and crises. Settlement contributes to local value creation and business development. Cultural life contributes to vibrant communities across the country. When people live and work in rural areas, jobs and economic activity are created that benefit the whole country. At the same time, however, many incidents require extensive collaboration, be it between municipalities, between municipalities and the business sector or between municipalities and others.

The Government is implementing a range of initiatives to increase the breadth of the municipalities’ preparedness work. This applies both to preventive work and to improving their ability to handle major undesirable incidents, crises and, in the worst case, war. These measures are described in more detail in Section 5.1.

Figure 2.5 The figure shows the percentage of the population of Norway and Sweden living north of the 60th parallel at the turn of the year 2023/2024

Source: Statistics Norway (for Norway) 1 January 2024 and Statistics Sweden (for Sweden) 31 December 2023. The figures in the table are based on the number of inhabitants in municipalities in Norway and Sweden, respectively, where more than half of the inhabitants live beyond the 60th parallel north.

2.2 Total defence and civil-military cooperation

Total defence encompasses mutual support and cooperation between the defence sector and civil society in relation to incidents in peacetime, crisis and war. It is a framework for use of our collective military and civilian resources to safeguard national security. Total defence will contribute to the utilisation of the country’s collective resources in prevention, preparedness planning, crisis management and impact management. This is important both for broad preparedness and for situations at the high end of the crisis spectrum. See Box 2.8 on the Norwegian total defence concept.

Textbox 2.8 The Norwegian total defence concept

The Norwegian total defence concept was developed in the period after the Second World War. In its report, the Defence Commission of 1946 emphasised the importance of strengthening the Norwegian Armed Forces by means of a total defence concept. The defence of Norway was to be based on both military defence and broad civil preparedness. The objective was, and still is, to protect Norway’s territory, independence and national values, and to protect the civilian population.

The focus of the total defence concept has changed over time however. During the Cold War, the focus of the concept was essentially in line with the 1946 Defence Commission’s recommendation, i.e. how the civil sector should support the Norwegian Armed Forces (war capability) in armed conflict while maintaining a minimum of civil society’s basic functionality and citizens’ fundamental security. After the Cold War, the focus shifted to how the Norwegian Armed Forces, as a significant preparedness resource in peacetime, could support civil society to ensure good preparedness and the best possible utilisation of society’s collective resources to tackle assignments at the lower end of the crisis spectrum. Among other things, this shift meant that several of the measures aimed at situations involving war, the threat of war or similar (known as war planning in civil preparedness) were discontinued during the 1990s and early 2000s. One example of this is the exemption from building emergency shelters in new buildings that has been in force since 1998. The current total defence concept was adopted by the Storting’s consideration of Proposition No 42 to the Storting (2003–2004) Den videre moderniseringen av Forsvaret i perioden 2005–2008 (The further modernisation of the Norwegian Armed Forces in the period 2005–2008 – in Norwegian only) , cf. Recommendation No 234 to the Storting and Report No 39 to the Storting (2003–2004) Samfunnssikkerhet og sivilt-militært samarbeid (Public security and civil-military cooperation – in Norwegian only), cf. Recommendation No 49 to the Storting (2004–2005), and includes mutual support and cooperation between the Norwegian Armed Forces and civil society in connection with prevention, preparedness planning, crisis management and impact management across the entire crisis spectrum from peace through security policy crisis to armed conflict.

Civil support for military efforts at the high end of the crisis spectrum (the original purpose) has gradually been given greater focus in recent years, especially after Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2014 (Donbas in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea).

Proposition No 87 to the Storting (2023–2024) The Norwegian Defence Pledge, underlines that the security policy situation must lead to total defence actors becoming more active in day-to-day life. This is necessary to avert and handle threats in the transitions between peace, crisis and war. One of the most important tasks of those involved in total defence is to function during war. It is therefore necessary to train and practise in peacetime. This also strengthens society’s overall resilience and endurance against hybrid threats, as well as other activities and incidents that present a threat to security in peacetime. Human capabilities are the most important resources in total defence. This is also reflected in the long-term plan for the defence sector, where one of the main priorities is a pledge to greatly increase personnel and expertise. Between now and 2036, the Government plans to recruit around 4,600 more conscripts, 13,700 more reservists and 4,600 more employees, and to boost expertise.

In principle, the term civil-military cooperation encompasses all civil-military cooperation at all levels and spans a very broad field and range of actors. In some cases, the Norwegian Armed Forces support civil activities, while in other situations the Armed Forces are supported by civilian resources.2 In situations lower down the crisis spectrum, civil-military cooperation, and cooperation with and the involvement of private actors and volunteers, is largely based on partnerships, voluntary schemes or binding agreements.

Today, the Norwegian Armed Forces play a significant and important preparedness role for civil society during peacetime. The Armed Forces assist in dealing with a number of different incidents, such as floods, landslides, various accidents and extraordinary events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. They also play a role in terrorism preparedness, and contribute by attending to regular day-to-day tasks for civil society. Examples include the rescue helicopter service, the border guard and the Norwegian Coast Guard, which carry out fisheries and catch surveillance, emergency towing response, customs inspections, environmental protection assignments etc. The Armed Forces also perform a number of assignments on request, to support the police or other public authorities and preparedness organisations responsible for public security, critical societal functions or critical infrastructure etc.

In situations at the high end of the crisis spectrum, society’s use of resources, prioritisation and the way it goes about its tasks will change significantly. Firstly, the Armed Forces will have to focus on their primary tasks, and the Armed Forces’ assistance to civil society may be downgraded or cease altogether. At the same time, the Armed Forces will be able to seize civil operational resources in such situations, such as rescue helicopters etc. These will, in turn, have less capacity to handle tasks in civil sectors. The Armed Forces will also increase its staffing level by mobilising the Home Guard and reservists in the rest of its structure. This means many people being pulled out of their daily life and civilian jobs.

Textbox 2.9 High on the crisis spectrum – prepared for war

The crisis spectrum is used as an expression of the range of undesirable incidents that could affect us. There is a wide range of potential incidents, and the severity and impact of a given type of incident, such as a cyberattack or a forest fire, can vary considerably. Armed conflict and war, i.e. situations where the nation’s security is under threat, are at the highest level of the crisis spectrum. Hybrid threats are a significant element in the current threat landscape. Hybrid threats may be present across the crisis spectrum (see Chapter 7).